on

Election Polling (Week 3)

Introduction

Polling has been an essential party of the run-up until elections for a number of decades now, and are a way of gauging national sentiment throughout the election. While polls do have error and have failed to correctly determine the winner, with the 2016 presidential election being the most salient example of this in recent memory, they continue to be a good barometer on national sentiment and have improved through methodological changes. Most major election predictions, like those by 538 and the Economist, use polls in addition to fundamentals like the economy in their model of the election (Silver 2020, Morris 2020). In this blog post, we’ll explore the addition of polls to the economic model that we built in last week’s blog.

Polling Across the Years

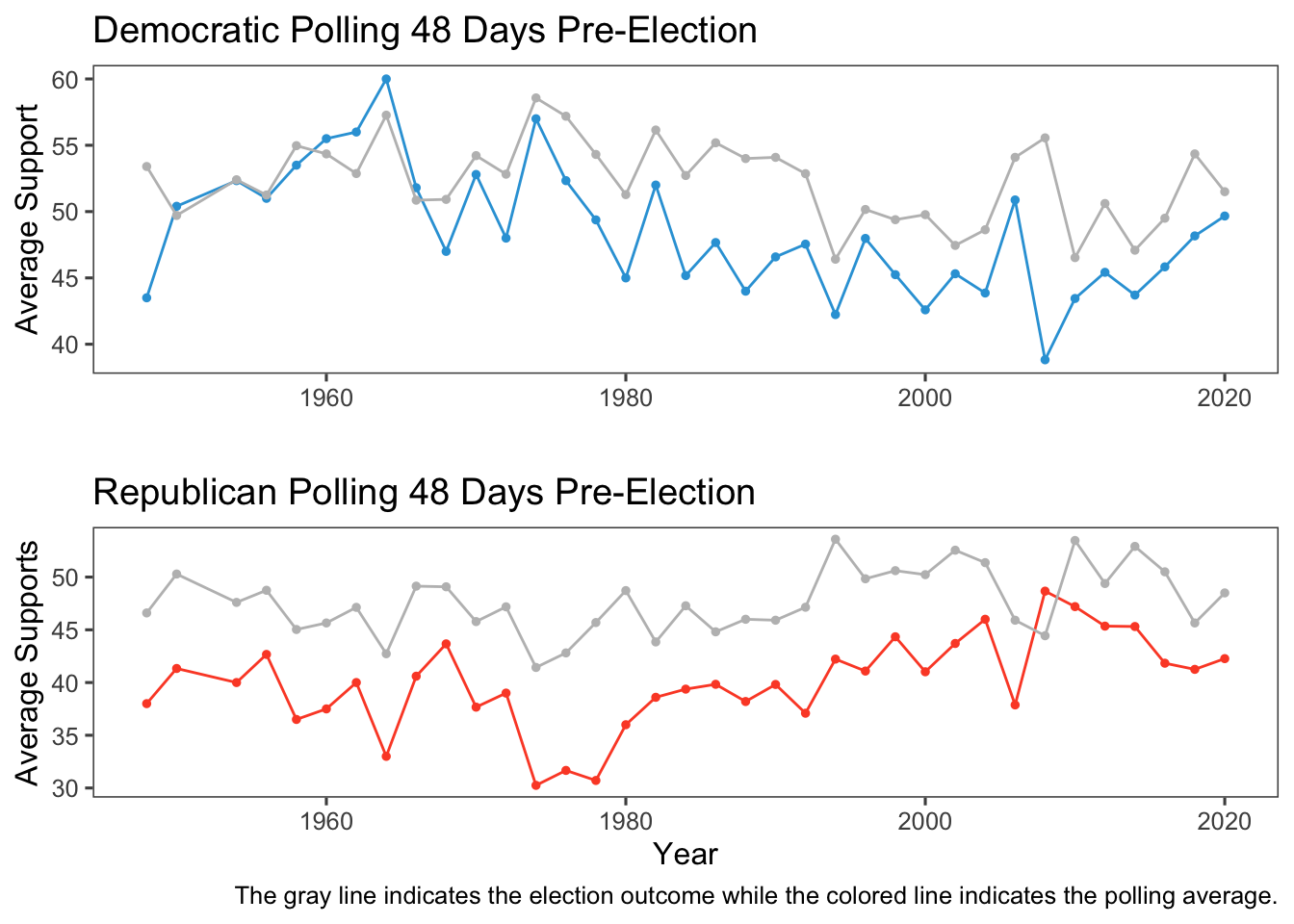

There is evidence that polling gets more accurate as it gets closer to the election. For the case of the US presidential election, it has been found that polls do not give additional predictive power more than 48 days out from the election (Jennings, Lewis-Beck, Wlezian, 2020). Thus, I’ll be averaging polls that are less than than or equal to 48 days from the election for this analysis. Plotted below is average generic ballot support for each party with their actual performance in gray.

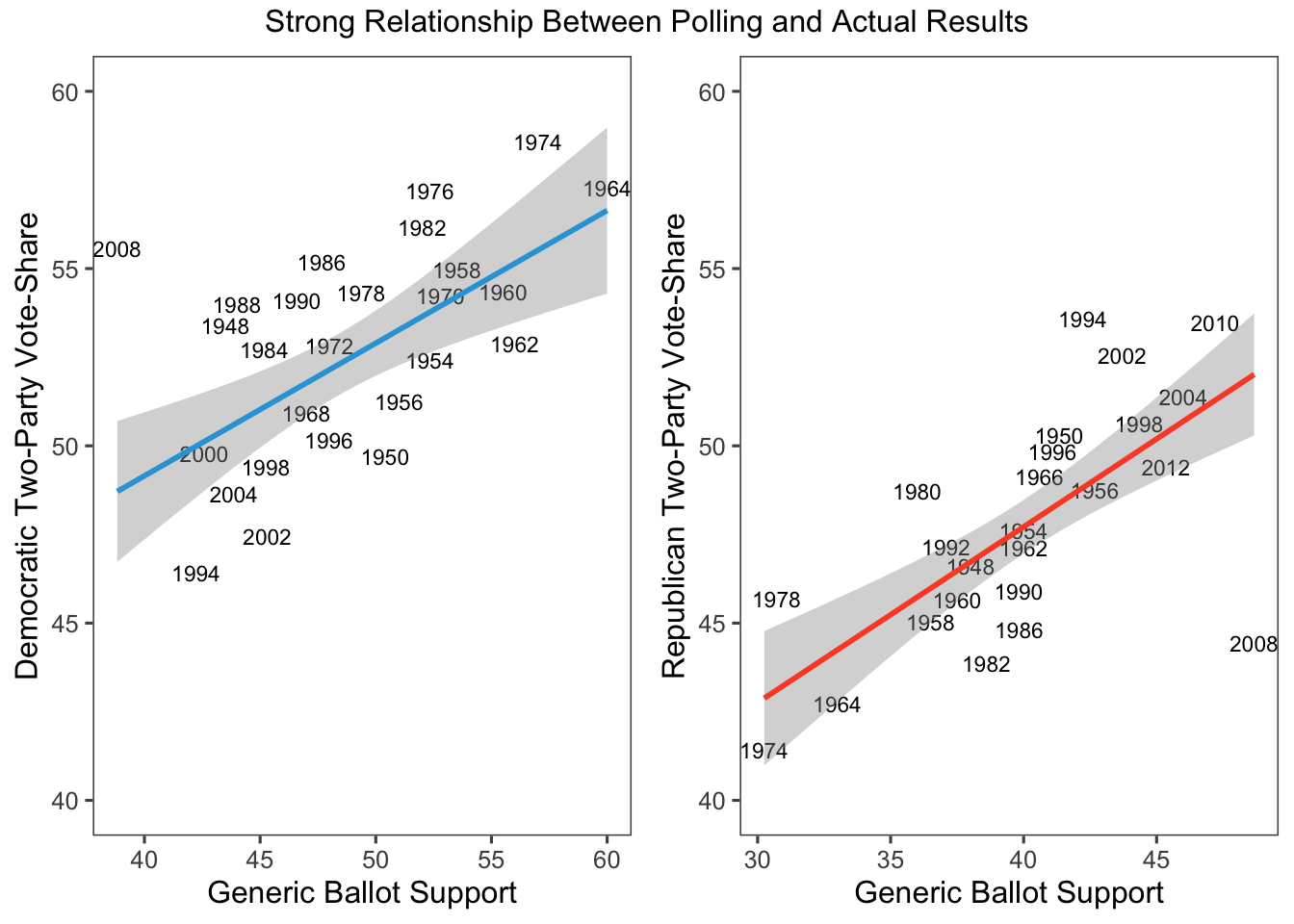

From the above graphic, we can see that while the polls do have a good amount of error year to year, the polling average, in general, travel with the actual results. We then take a look at the actual relationship between the polling average and election results to find that it is very strong, with the exception of the year 2008, where polls were very off, possibly due to the recession.

## Warning: The following aesthetics were dropped during statistical transformation: label

## ℹ This can happen when ggplot fails to infer the correct grouping structure in

## the data.

## ℹ Did you forget to specify a `group` aesthetic or to convert a numerical

## variable into a factor?

## The following aesthetics were dropped during statistical transformation: label

## ℹ This can happen when ggplot fails to infer the correct grouping structure in

## the data.

## ℹ Did you forget to specify a `group` aesthetic or to convert a numerical

## variable into a factor?

Generic Ballot Polling Model

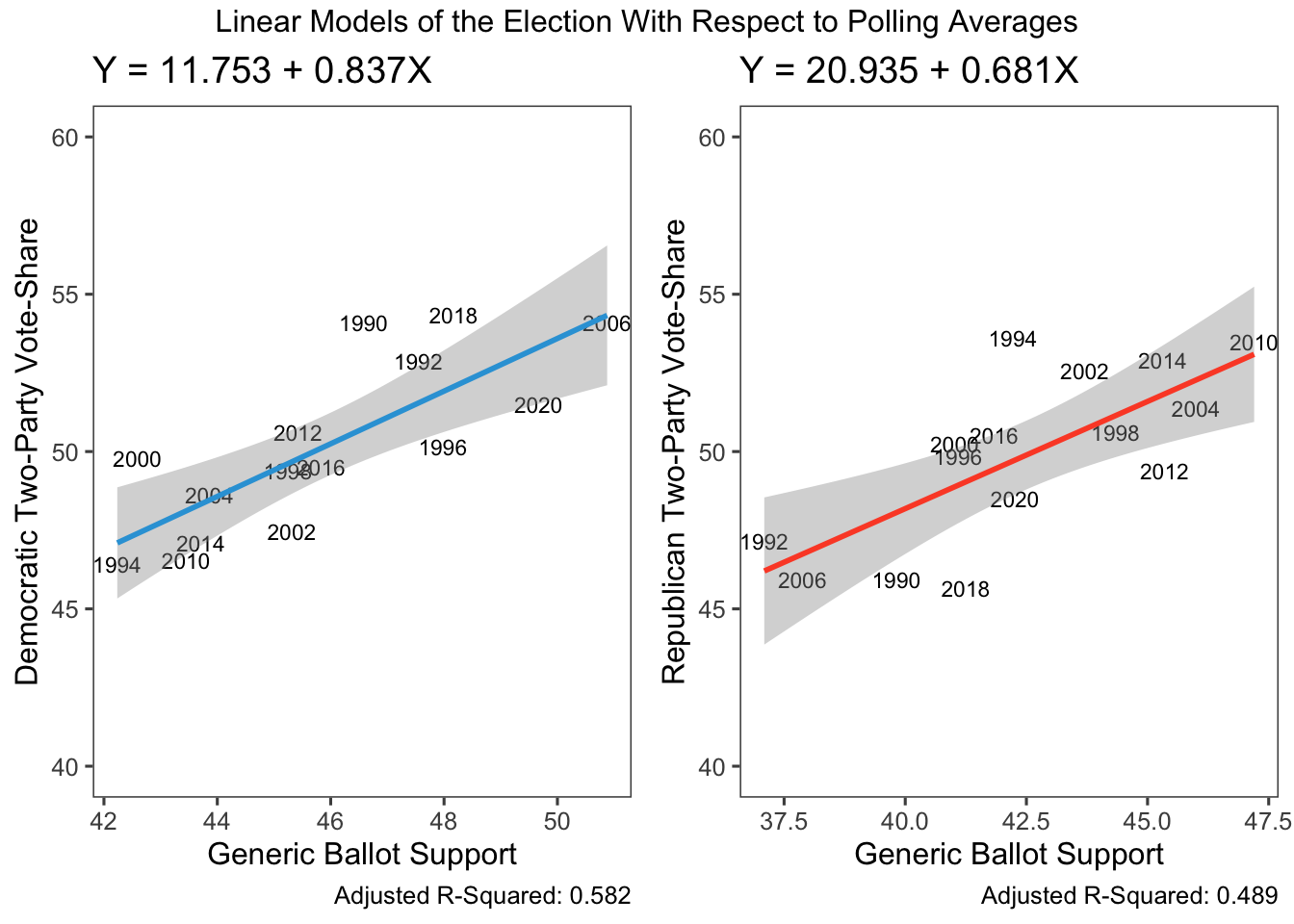

For the purposes of this model, we’ll remove 2008 as an outlier and take only polls from 1990 onwards. This is because we want a more recent set of years to take advantage of improvement in polling methodology and quantity of polls. We choose 1990 onwards because that is when the House became competitive between the Democrats and Repuclicans. That means that a univariate regression would look something like this:

## Warning: The following aesthetics were dropped during statistical transformation: label

## ℹ This can happen when ggplot fails to infer the correct grouping structure in

## the data.

## ℹ Did you forget to specify a `group` aesthetic or to convert a numerical

## variable into a factor?

## The following aesthetics were dropped during statistical transformation: label

## ℹ This can happen when ggplot fails to infer the correct grouping structure in

## the data.

## ℹ Did you forget to specify a `group` aesthetic or to convert a numerical

## variable into a factor?

Comparison of Different Approaches from 538 and the Economist

At this point, we could make a prediction of the election using a polls-only model. Indeed, whether fundamentals like the economy should be included into a model of the election, and to what extent, is an area of significant debate and research. For example, Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight, describes in his methodology for the 2022 election that they have three different models, one with just polling (plus inferences for districts without polling), one with polling and fundamentals, and one with polling, fundamentals, and expert predictions. Silver writes that the preferred FiveThirtyEight model is the “Classic”, or the one with polling and fundamentals, for its increased accuracy over the just-polls model from 1998 to 2016, and for its independence from other predictions (Silver 2022). G. Elliot Morris, in his description of the 2020 Economist model, is similar in his usage of both polling and fundamentals to predict the election. Morris writes that they use a Bayesian model, with fundamentals as a prior, that they update as more polls are done closer to the election (Morris 2020). These models are both very sophisticated, with carefully tailored algorithmic adjustments made to polling and election data based on each group’s research and decisions on election forecasting. While the Economist made public their model and data, FiveThirtyEight did not, so while I prefer how FiveThirtyEight has multiple models with different inputs for it’s consideration of the importance of fundamentals, it’s uncertain what their model is “under-the-hood” and thus it’s hard to say I prefer one over the other.

Predicting the Election

In our case, we’ll be using a much simpler model. We’re currently 43 days away from the midterm election, which puts us at a comfortable point relative to our 48-day average model. The 538 generic ballot polling average for Democrats is 45.2% and for Republicans is 43.6%. Using the polls-only linear model defined above, that means that we expect Democrats to win 49.6% of the two-party vote and Republicans to win 50.6% of the two-party vote. This unfortunately doesn’t sum to 100% of the vote, but it gets pretty close and predicts a Republican popular vote victory.

Combining this with our previous economic model to build a polling and fundamentals model is more difficult than it at first seems. Polling data is better at predicting the share of votes each party will receive, while our model of the economy is highly tied to incumbency. Because the polls model does better, in general, than the economic model, for the purposes of model combination, I predict for the two-party share of Democrats. I go through a similar model selection as described in the last post to get the following model combining fundamentals and polling:

##

## ===============================================

## Dependent variable:

## ---------------------------

## D_majorvote_pct

## -----------------------------------------------

## average_support 0.833***

## (0.165)

##

## GDP_growth_pct -1.430*

## (0.676)

##

## UNRATE -0.372

## (0.276)

##

## Constant 15.070*

## (7.932)

##

## -----------------------------------------------

## Observations 15

## R2 0.746

## Adjusted R2 0.677

## Residual Std. Error 1.560 (df = 11)

## F Statistic 10.759*** (df = 3; 11)

## ===============================================

## Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01This model gives the prediction that Democrats will win 50.8% of the popular vote, making them the victor in terms of popular vote, which is different from our polls-only model.

## fit lwr upr

## 1 50.84872 48.16312 53.53433Conclusion

Overall, we find conflicting results from our polls-only and polls-plus-economy model. In comparison, the latter model has greater predictive power (with an r-squared of 0.677 in comparison to an r-squared of 0.582) and follows the path of other forecasters in including fundamental variables. This model also improves upon the economy-only model from last week, with the largest changes coming from adding polling averages, removing the 2008 election as an outlier, and keeping only years after 1990. Still, there is more fine-tuning to be done to further improve the model that will be done in the coming weeks!