on

Media and Campaigns (Week 5)

Introduction

So far, the blog posts have covered things that are largely outside the direct control of campaigns - to the tune of the economy, polling, and expert predictions. We now move to something that campaigns can directly control - the air war, or that advertisements that campaigns will put out on television. We know from previous research that television ads can and do affect voters, particularly through priming voter preferences, though these effects may only be on the short-term (Gerber, 2011). It is possible, however, that conflicting advertising will simply cancel itself out. There are also many regions of the country that receive next to no advertising due to their lack of competitiveness. This blog post will take a look at the significance of the media war in elections.

Overview of Campaign Media Operations

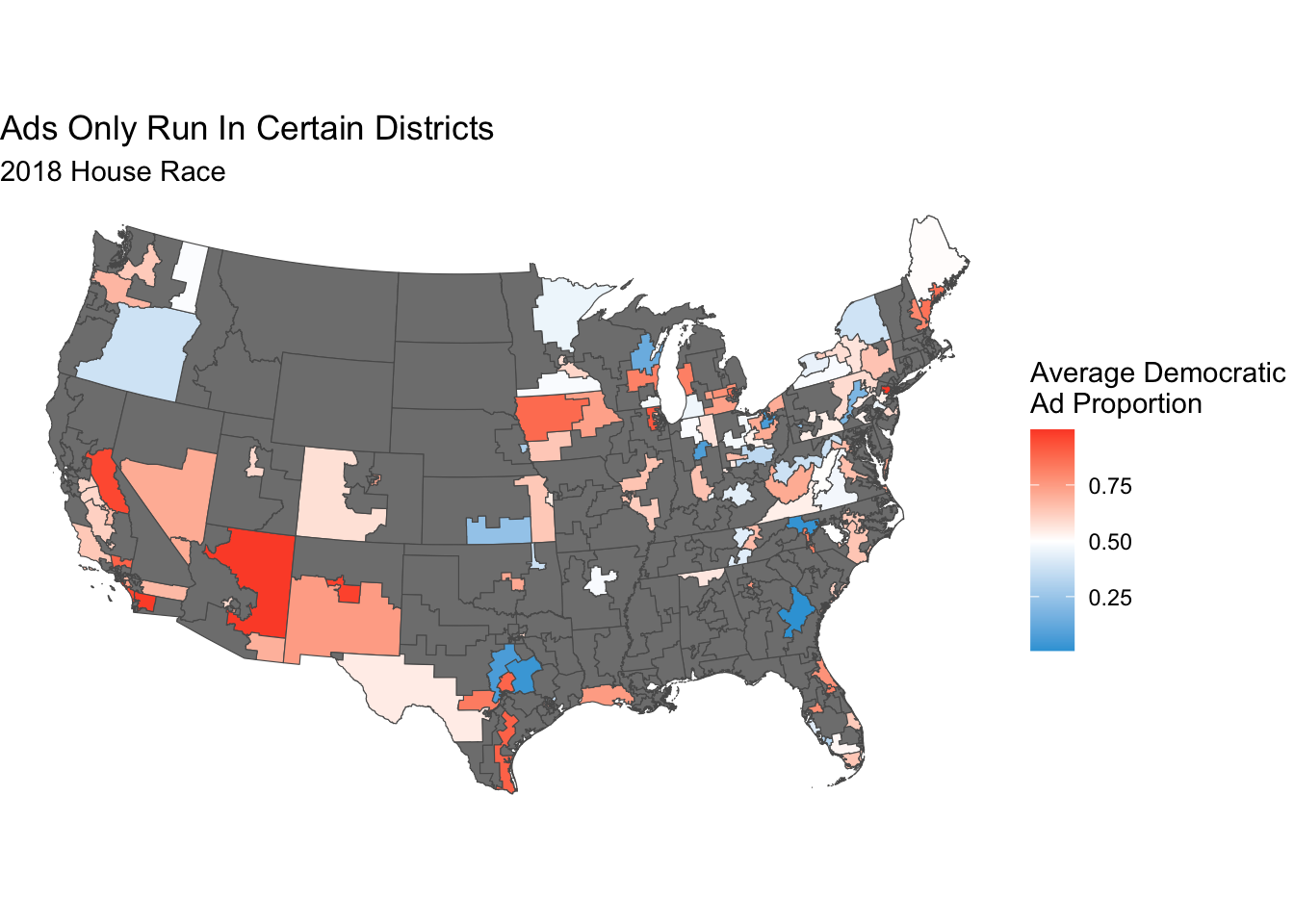

TV ads are an aspect of the campaign that can be highly controlled due to their nature. Their message can be crafted detail to target a specific subset of voters. They’re expensive, however, which means that only the districts that are the most competitive are going to have any amount of advertising at all. Below is a map of all the districts that have had ads run in them in the 2018 midterm election, and the share of ads run that were Democratic in nature. We see that only a small subset of districts have ads run in them, and that a lot of the districts seem to be contested (both Democrats and Republicans are running comparable numbers of ads).

Modeling the Election with Media Data

In order to build our district-level model, we first take ad data from 2006 to 2016 and find the average Democratic ad proportion. Then, we model each district according to the relationship between the percentage of the vote that the Democratic politician received with two variables - the share of Democratic ads, and the share of stations that are playing Democratic ads. We then take only districts that have at least four years of advertising data outside of 2018.

Model Results

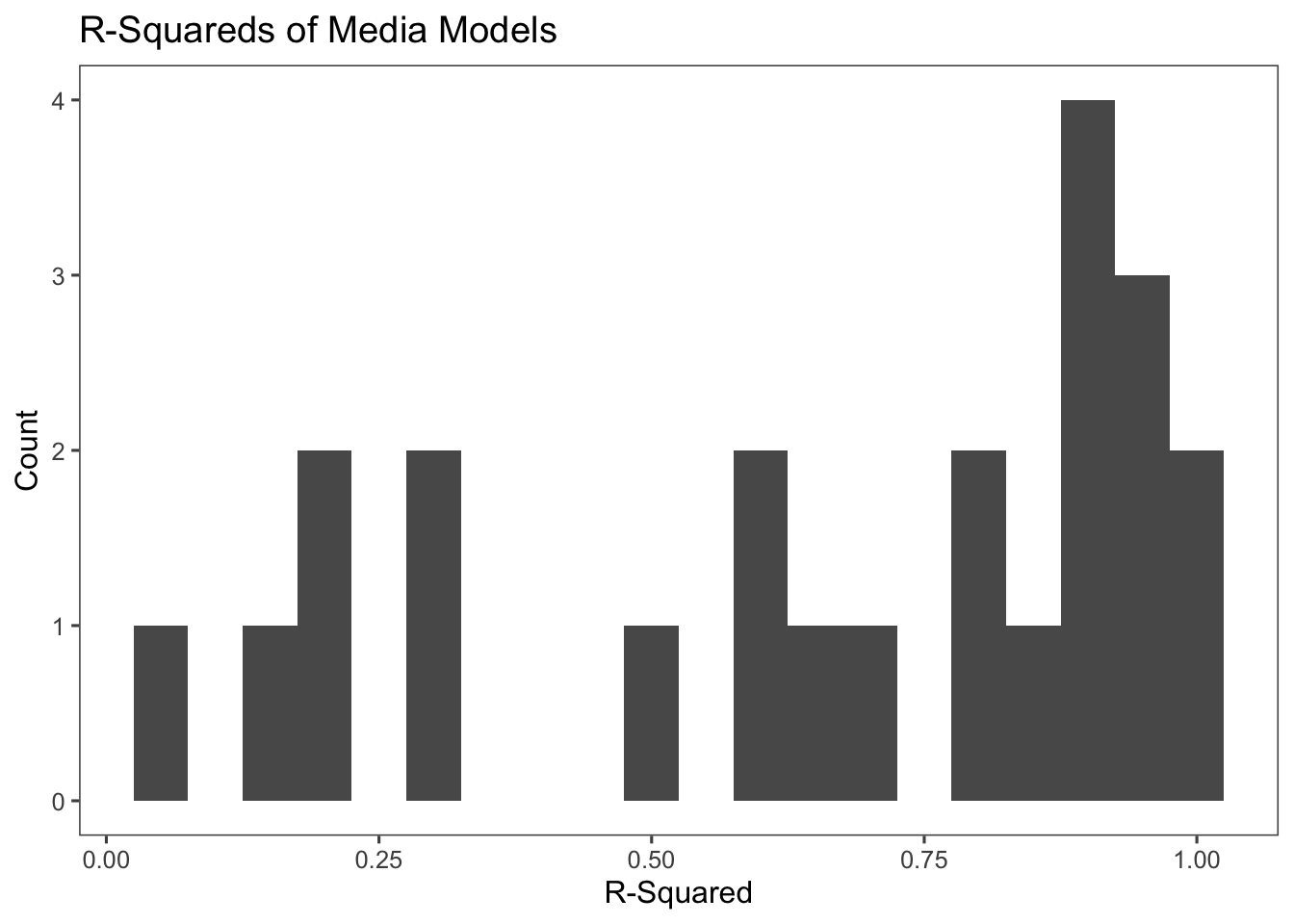

Overall, these models weren’t great. A good number of them had very low predictive power and others had near perfect predictive power due to a lack of variation in the outcomes of those districts. That means that of our already small number of models due to lack of data, we have even less data to use when it comes to modeling the relationship between media and election results. Below is a graph of the calculated r-squareds from each model.

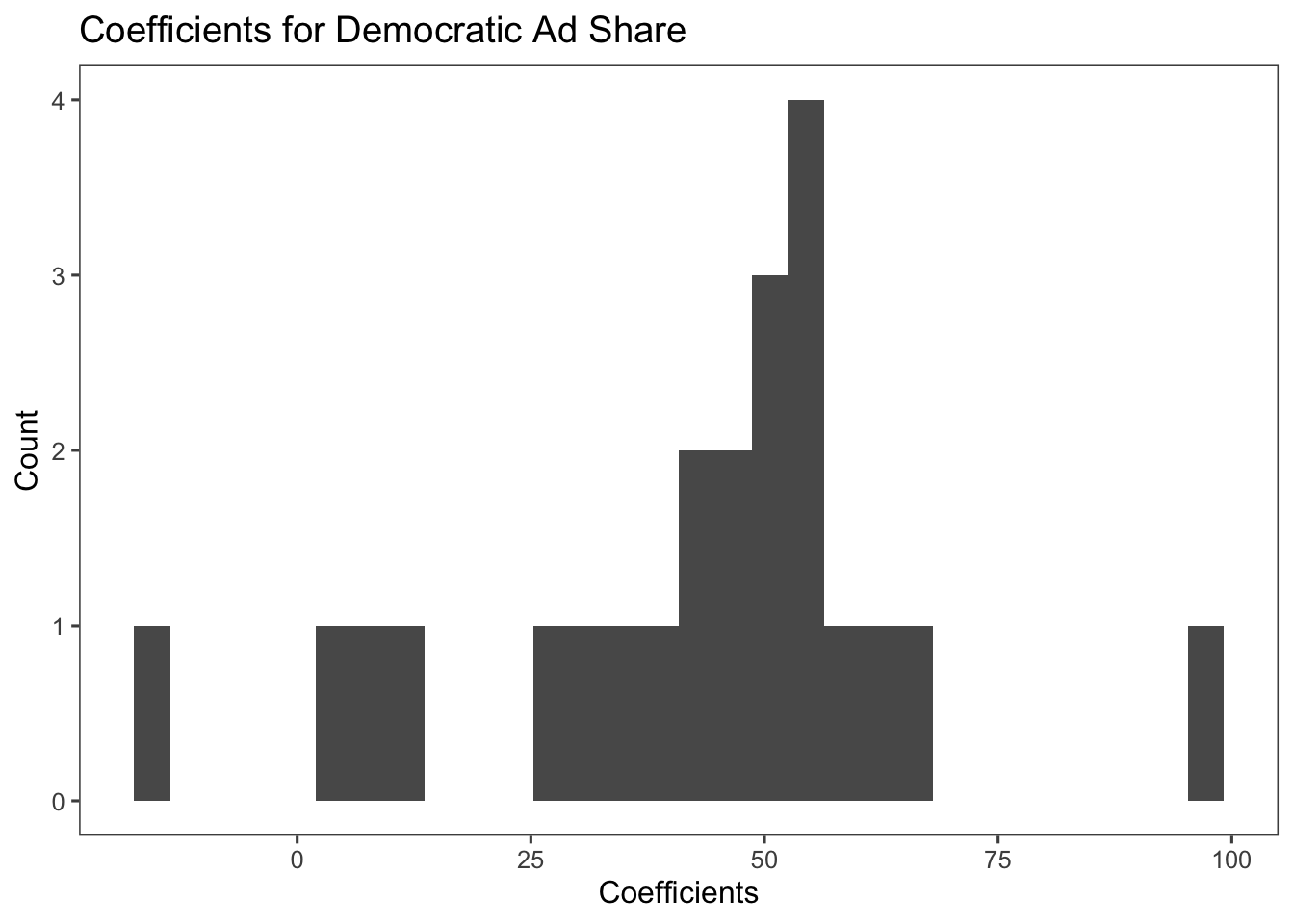

The coefficients for Democratic ad share are positive, which tells us that the higher proportion of Democratic ads in a district, the higher the proportion of Democratic votes, which makes intuitive sense. This is shown in the graph below. It seems that on average, increasing the proportion of Democratic ads by 0.1 would lead to a nearly a 5% increase in the vote share for Democrats. The issue is that these coefficients are only a small subset of the districts since we dropped the districts that lacked data, but it seems to indicate that in general trends are positive.

Conclusion

From looking into the effect of media on election results, it seems that the data is somewhat consistent with what we believe intuitively: running more ads than your opponent leads to increased votes. However, due to the lack of data in many disitricts and the short timeframe, I was only able to build media models for 23 of the 435 districts. This dimension of election data is interesting, but because of lack of usable data, I will not be including it in my final election model.