on

Final 2022 Midterm Election Prediction

Introduction

My final prediction for the election is a product of research and investigation through the series of blog posts that I have done prior to this week, investigating how factors like polling, the economy, and incumbency affect election results. As my final model, I use an ensemble model that combines two main things - first, a pooled model that contains the last decade of elections, and second, a partisan lean for the district that is calculated through recombining election results in the new district post-redistricting.

Pooled Model of Fundamentals, Polls, Expert Predictions

For the pooled model, I use data across all the districts in order to build one model to create predictions for the Democratic two-party vote-share in each district. This final model is specified below:

| Pooled Regression Model | |||

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI1 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| average_support | 0.28 | 0.23, 0.33 | <0.001 |

| house_party_in_power_at_election | -2.0 | -2.4, -1.5 | <0.001 |

| pres_party_in_power_at_election | -3.5 | -3.9, -3.1 | <0.001 |

| prev_results_dist | 0.33 | 0.32, 0.34 | <0.001 |

| avg_rating | -4.4 | -4.6, -4.3 | <0.001 |

| incumb | 3.3 | 2.5, 4.1 | <0.001 |

| gdp_percent_difference * incumb | -0.22 | -0.29, -0.15 | <0.001 |

| R² = 0.721; Adjusted R² = 0.721; No. Obs. = 14,436 | |||

| 1 CI = Confidence Interval | |||

The variables used are as following:

average_support: This takes an average of generic ballot polls in the last 45 days before the election. The polls are pulled from 538 and measure what national sentiment is like when it comes to each party. Here, we see a positive relationship as expected, where Democrats do better in elections when they’re doing better in generic ballot polling.

house_party_in_power_at_election: This looks at which party is the incumbent party in the House at the time. We see that Democrats holding the House tends to mean that they’ll do worse the next election.

pres_party_in_power_at_election: This looks at which party is the incumbent party in the Presidency at the time. We see that Democrats holding the Presidency also tends to mean that they’ll do worse in the next election.

prev_results_dist: This is how the district performed in the previous election. As expected, if Democrats did better in the district in the last election, then they are predicted to do better in the next one as well.

avg_rating: This is a combination of ratings from the Cook Political Report, Inside Elections, and Sabato’s Crystal Ball. This is on a 1-7 scale, where 7 is strongly Republican. As expected, a higher prediction drops the predicted Democratic vote-share.

incumb: This is a measure of incumbency for the specific seat based on party. Where there is a Democratic incumbent running, Democrats tend to do better.

gdp_percent_difference*incumb: This interacts the change in GDP from Q6 to Q7 with incumbency, based on the theory that voters will punish the incumbent for a bad economy. We find here a negative relationship between this variable and Democratic seat share.

The final adjusted R-squared for the model is 0.721, indicating that 72.1% of the variation in the data is explained by this model. When we use bootstrapping on this model, resampling the data with each iteration, we get an r-squared value of 0.719, which is very similar to our adjusted R-squared from the model and indicates consistency.

With just this pooled model, the prediction is that Democrats will win 216 of the seats, which means that Republicans will control the House. When looking at the upper and lower bounds of the predictions for every district in this model, the results largely don’t change. The upper bound has Democrats at 217 seats while the lower bound has Democrats at 213 seats. Thus, this model tells us that the House will likely be very close, but have a narrow Republican victory.

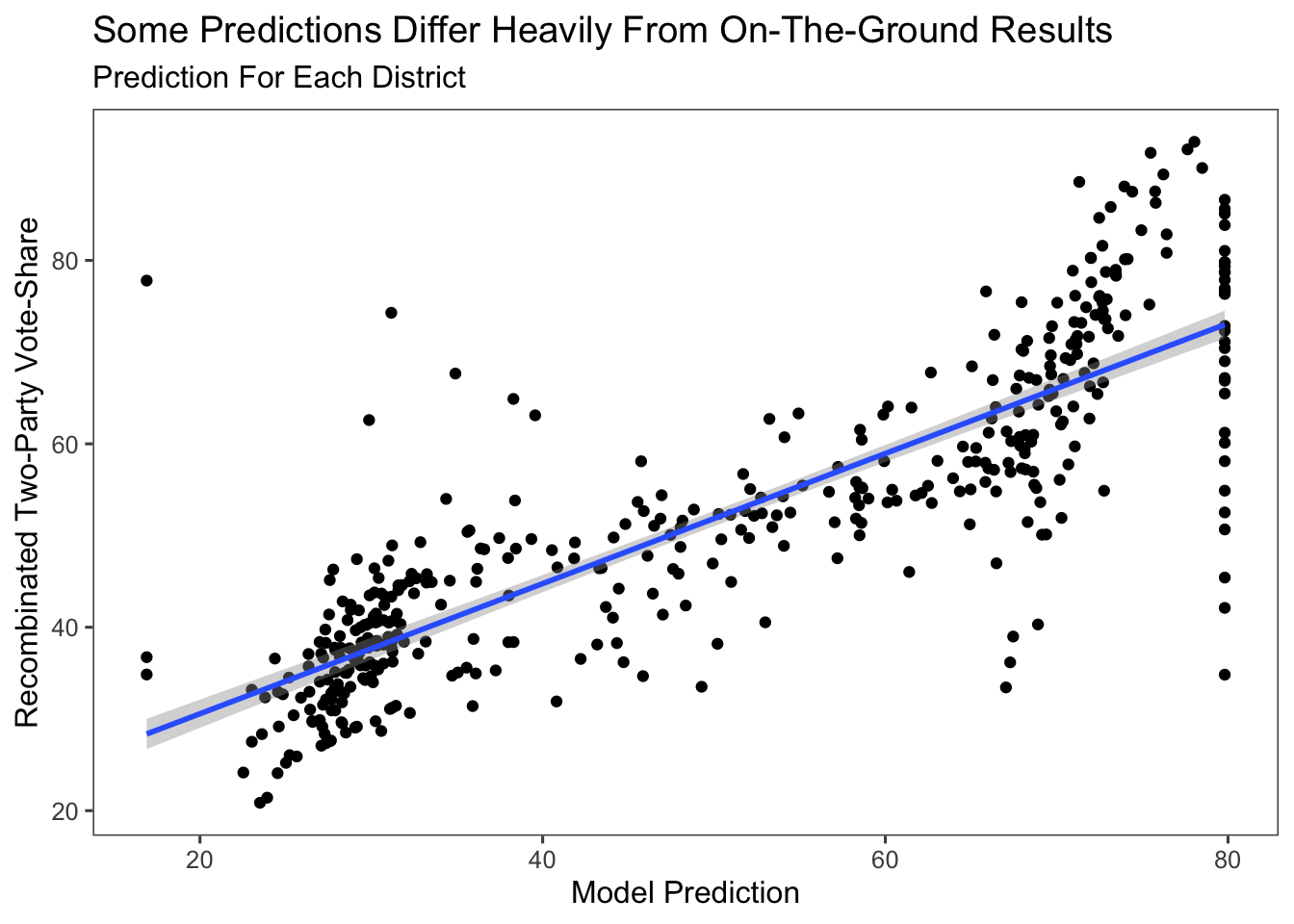

Adding in Redistricting

The largest flaw in the previous model is that it doesn’t take into account redistricting. There are cases where the district is completely different from how it once looked due to changes in the redrawing of boundaries. The plot below shows all of the predictions of the model plotted against the Democratic Two-Party Average in the district post-redistricting. As an example, Georgia’s 13th District is the point in the top right corner of the plot. It was previously a very red district, but now shares no geographic overlap with the former district and instead is solidly Democrat. This is an example of a district that our model gets almost completely wrong.

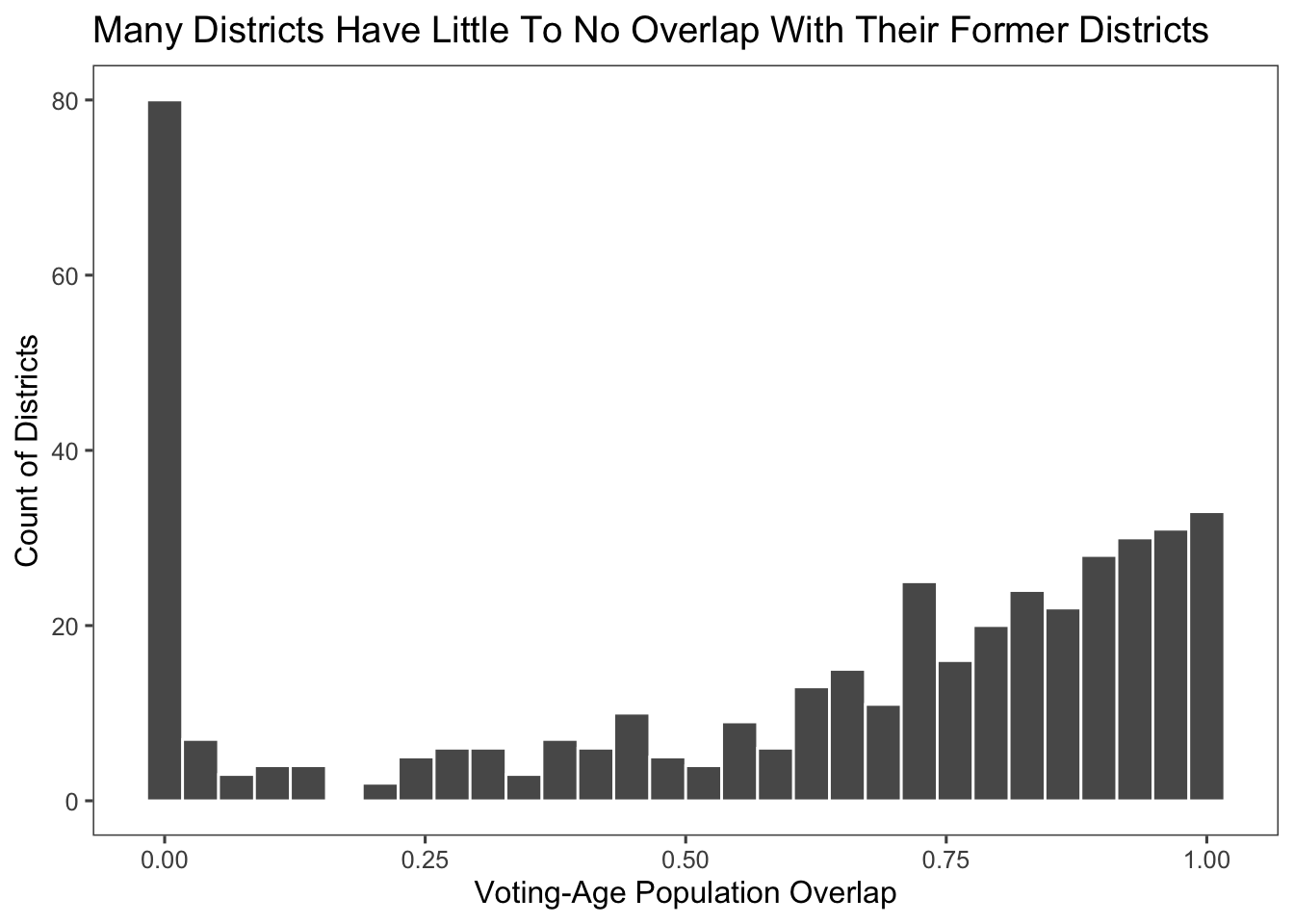

Below is a histogram depicting the percentage of the population that overlaps between the pre- and post-redistricting districts. As is shown, predicting a district this year with information about the district in the past is a faulty errand.

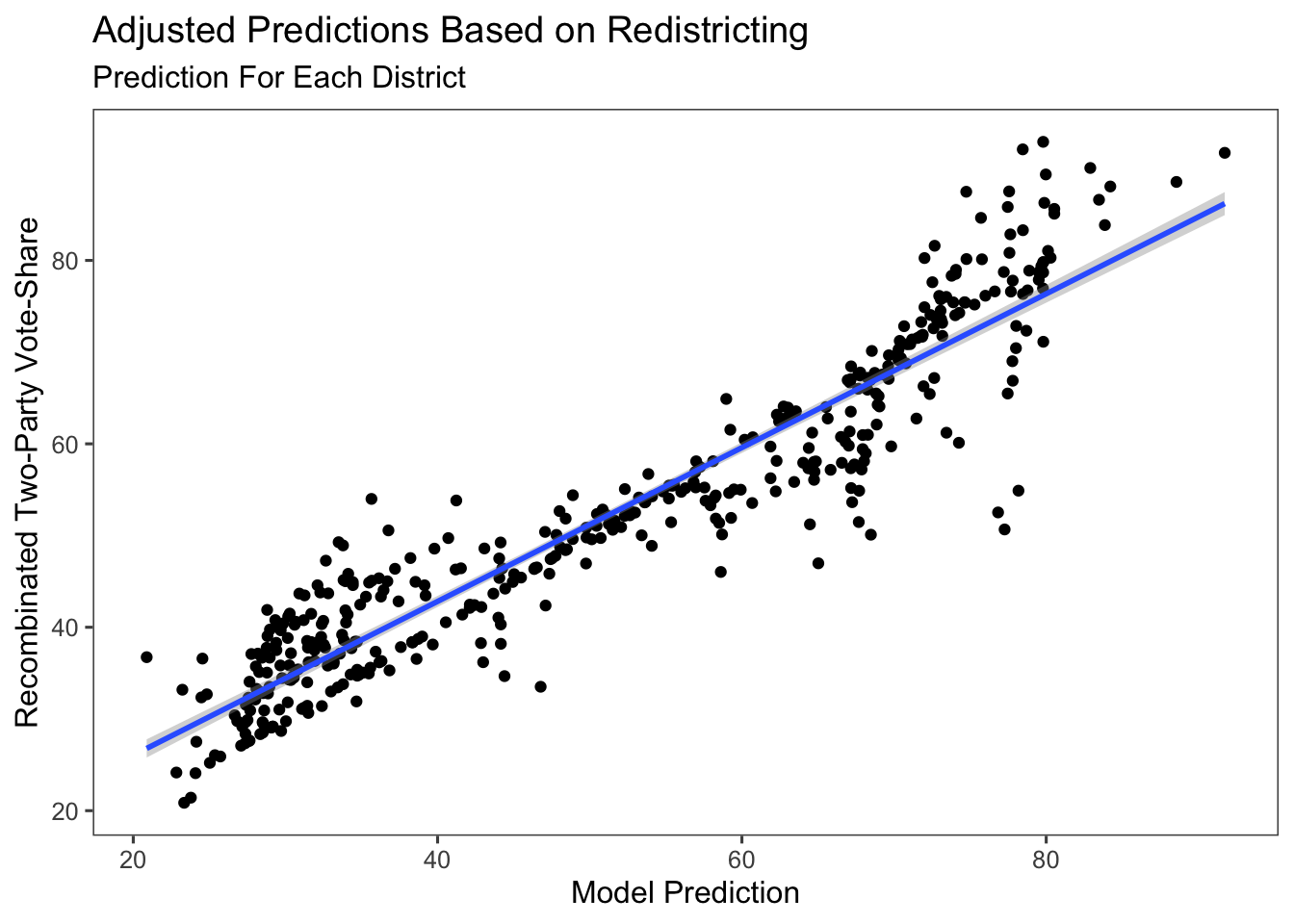

Thus, in order to fix this, I take the model prediction and weight it by how much the population overlaps from the old and new districts. I then make up the rest of the prediction with the average partisan lean over the last three elections. I do this in order to use information from the model predictions, but where this is not much, to supplement that with the partisan lean of the district.

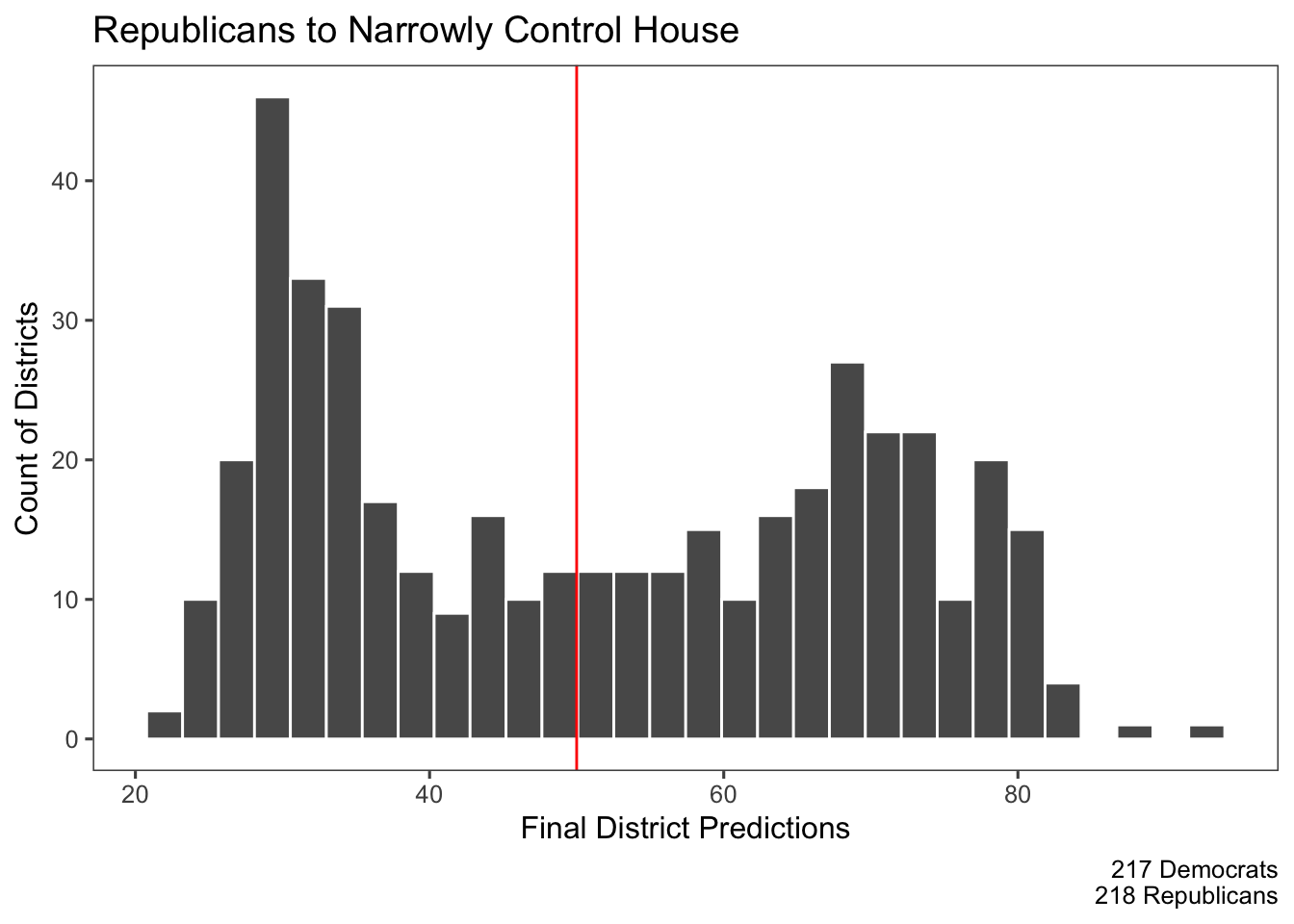

The final prediction tells us that Republicans will narrowly control the House with 218 seats to Democrats 217 seats, but that Democrats will win the popular vote with 51% to Republican’s 49%.