on

Reflections on Final Election Predictions

Introduction

Now that the election is over, it is possible to evaluate how my model has done when it comes to the election. First, I’ll take a look at overall measures of accuracy, then look at district-level accuracy, then explore trends in the misses and the correct calls that I made for the election.

Model Evaluation

To begin with, there is an important error that I only caught after the election itself. I did not predict the eight new districts created this election through redistricting - instead mistakenly predicting for eight older districts that now no longer exist. First, I’ll evaluate my model by ignoring these districts, then, I’ll predict these districts as I would have with my final model and do model evaluation in that way.

First, when evaluating the model without the eight unpredicted districts, we find that the root mean squared error hovers around 10 for the model with redistricting and 13 for the model without the redistricting adjustment. This means that the weighted average error between the predictors and the actuals is 10 points, which is okay given that the predictions are on a range of 0-100. We do find here that the redistricting model performed better than the model without the redistricting adjustment. As a comparison, both models outperformed directly using the previous vote share for the district in the last election, but the pooled model without redistricting actually did worse in comparison to using just the straight partisan lean for the district. The modeled predictions with the redistricting adjustment did narrowly better than just using the straight partisan lean for the district.

| RMSEs for Each Model Created | |

| Disregarding 8 Unpredicted Districts | |

| Model | RMSE |

|---|---|

| Predictions w/ Redistricting Adjustment | 9.93 |

| Predictions w/o Redistricting Adjustment | 13.31 |

| Lower Prediction Bound | 13.26 |

| Higher Prediction Bound | 13.38 |

| Average Partisan Lean (Control) | 10.21 |

| Previous Results (Control) | 17.43 |

The additional predictions, because they are made in districts with no previous history, entirely consist of using the average partisan lean from the old districts that they were made up of. Many of the predictions come very close to the actual results and the only district that is predicted incorrectly is Florida’s 28th district.

| Districts Not Predicted | ||

| Prediction of Democratic Two-Party Vote-Share | ||

| State & CD Fips | Actual Results | Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| 0808 | 50.36% | 51.53% |

| 1228 | 36.31% | 52.57% |

| 3001 | 48.36% | 48.50% |

| 3002 | 26.28% | 39.43% |

| 3714 | 57.71% | 56.73% |

| 4106 | 51.23% | 53.76% |

| 4837 | 78.54% | 74.34% |

| 4838 | 36.02% | 36.58% |

The final results of my prediction after correcting these errors is actually further from the actual results. Here I predict that there will be 219 Democratic seats and 216 Republican seats, as opposed to the original incorrect 217D-218R seat prediction. The root mean squared error with these corrections is 9.89, which is narrowly better than the 9.93 in the model without corrections.

District-Level Accuracy

My final model with redistricting adjustments miscalled 17 districts (~4% of the districts). In 12 of these districts, I was overconfident in the direction of Democrats. Some of these misses were relatively close - about 1-2% off - and could be largely attributed to the fact that these district were swing districts. There were a couple of districts, however, where I was off as many as 18 percentage points. There also appears to be some systematic misses. In particular, I tended to miss a lot of districts in New York and California, predicting them to be substantially more Democratic than they actually were.

| Incorrectly Predicted Districts | ||||

| Prediction of Democratic Two-Party Vote-Share | ||||

| State | District | Actual Results | Prediction | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 13 | 49.66% | 55.54% | −5.88% |

| California | 22 | 47.33% | 57.00% | −9.66% |

| California | 27 | 46.73% | 54.81% | −8.07% |

| California | 45 | 47.54% | 53.66% | −6.12% |

| Florida | 28 | 36.31% | 52.57% | −16.25% |

| Maine | 02 | 51.80% | 49.76% | 2.05% |

| Nebraska | 02 | 48.66% | 51.25% | −2.59% |

| New Mexico | 02 | 50.35% | 48.89% | 1.46% |

| New York | 03 | 45.87% | 56.01% | −10.14% |

| New York | 04 | 48.12% | 62.28% | −14.16% |

| New York | 17 | 49.53% | 67.71% | −18.18% |

| New York | 19 | 48.87% | 50.72% | −1.85% |

| North Carolina | 13 | 51.59% | 49.79% | 1.81% |

| Ohio | 01 | 52.46% | 48.01% | 4.45% |

| Oregon | 05 | 48.88% | 52.06% | −3.19% |

| Virginia | 02 | 48.29% | 50.13% | −1.84% |

| Washington | 03 | 50.47% | 38.22% | 12.25% |

I do consider this a success! I actually had a 96% classification rate and miscalled less districts than both the Economist (18 miscalled districts), and 538 (23 miscalled districts). There appear to be some trends in the districts that I tended to miss. Many of the districts are very close - ME02, NE02, NM02, NC13, and VA02 all are within 2 percentage points of my predictions. In New York and California, however, I missed the prediction by as much as 18%. I am not alone in this - the districts that I miscalled were also districts that tend to be miscalled. New York performed particularly bad for Democrats due to mismanagement by the New York Democratic Party and court-ordered changes to redistricting. Similar issues in California also led to much fewer seats that predicted.

Below, I compare the districts that I called wrong to predictions from 538, The Economist, and the Cook Political Report. Here we see that many of the districts that I called wrong were similarly called wrong by other expert predictions. In particular, there are 7 districts that were called incorrectly across the board.

| Incorrectly Predicted Districts | ||||

| Comparison with Experts | ||||

| State | District | 538 Error | Economist Error | CPR Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| California | 22 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| California | 27 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| California | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Florida | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maine | 02 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nebraska | 02 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| New Mexico | 02 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| New York | 03 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| New York | 04 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| New York | 17 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| New York | 19 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| North Carolina | 13 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ohio | 01 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Oregon | 05 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Virginia | 02 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Washington | 03 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Interestingly, the model without redistricting had a closer call in seat share by one seat, but had nearly twice as many incorrect seats called (33 miscalled seats). This indicates that, at least for my model, redistricting somewhat canceled out nationally in terms of partisan seats. Nonetheless, adding redistricting into my model improved the accuracy significantly.

Prediction Trends

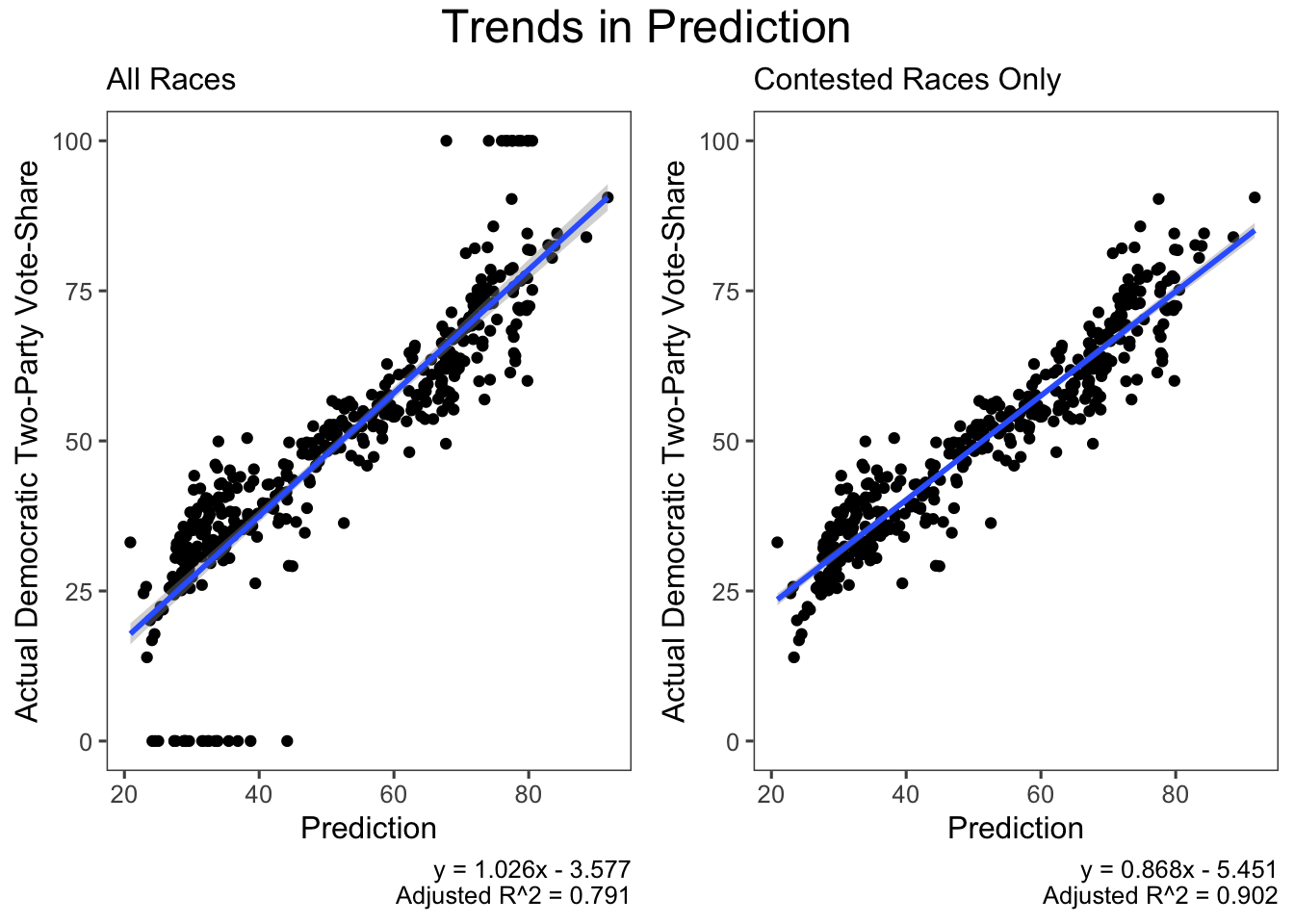

Below, I’ve plotted my predictions against the actual democratic two-party vote share. The obvious first thing to have done to improve the model would be to impute the values where the race was uncontested. The model did relatively well in predicting them - there were no unexpected uncontested races where the winner would not have been obviously from on party or another. This would have dropped the root mean square error to 5.78 from 9.89, nearly cutting it in half.

The other adjustment that I would have made to my model is to include some kind of variable for the quality of the campaigns that were run. Something that would’ve potentially captured the variation this cycle is the amount of capital that each of the campaigns had access to. In particular, mismanagement and lack of support typically means that there is a lack of funding for the campaigns. To test for this, I could retroactively test and see whether there is a relationship between how well a campaign did over a fundamentals model (with partisan lean from redistricting in the model) and how much money their campaign spent (looking at FEC data).